Part 1 — Sales as Strategy: A Radical Proposal for Rethinking Corporate Evolution

Sales is the stepchild of business. That’s why it’s the “S” lumped in with “G&A” on so many financial reporting structures.

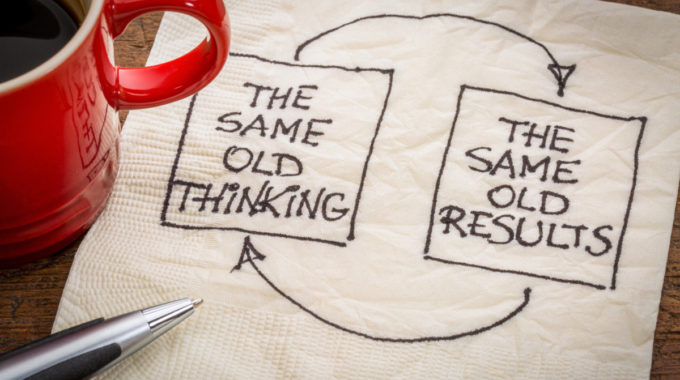

Given the obvious importance of sales, why is this? It’s simple, really. Businesses are generally conceived of as static entities that make products at ever-decreasing costs due to economies of scale — businesses for which the cost of the nth widget is slightly less than the n–1 widget. Given that economies of scale are reliable, and consumer tastes and needs have historically been slow-moving compared to the cycle time of making another widget, it made sense for companies to consider themselves at the center of their own solar system, a sun radiating products that must be distributed like light to the surface of the planets (aka consumers and customers) surrounding them.

In this traditional conception of business, then, the primary weapon of strategy was the “merger” — or, less politely, the “acquisition.” Buy a company, and you have more scale. The idea is that two suns could become one, shining more brightly per unit of fuel (capital) consumed to make their light (products). The “merger effect” is given the name “synergy.” Synergy, in practice, is usually mere cost-cutting in core services by eliminating redundant infrastructure and the extra people it takes to manage, and sometimes to execute, overhead functions: if you put everyone in one building, you don’t need any more light bulbs, especially if “everyone” excludes a whole bunch of folks, generally from the acquired company, whose output is now “redundant.”

Wherefore art thou merging?

Hence, corporate strategy mostly consists of buying companies like oneself that confer some imagined advantage. Perhaps they serve a geography you don’t serve very well or at all. Or maybe they have moved ahead of you in incorporating an important new technology in their products, but you have more money to sell their cool newness to your bigger market. Or maybe they are valued at a lower multiple of profit, or revenue (for the fast-growing), and you can wrap their financial results in your valuation cloak to make money from, well, nothing. Or maybe you’re tired of competing with them and would rather have a little more pricing authority (which can get dicey with the authorities, but only occasionally, and usually late in the game).

In all these cases and more, the strategic moves that define the evolution of most companies look a lot like buying other companies. And given that entrepreneurs have a strange compulsion to make new companies, and venture capitalists have no choice but to fund some of them (quaintly called “putting money to work”), the game appears to be able to go on forever.

And (here’s the important part for this discussion) sales doesn’t play a role in any of this.

Or does it?

When good intentions go bad

Let’s add one more fact. Almost every acquisition fails to achieve its goals as laid out at the time someone decided it was a great idea. Now, the cost-cutting “synergies” almost always work out. The integration of operating systems usual does too, often in some weird and bastardized Rube Goldbergian way that reflects the reality of systems, where the description rarely matches the mathematical reality. But the successful generation of all those wonderful, new revenue dollars from selling B’s products through A’s sales channels into all those ripe markets? Not so much.

Why not?

It’s not for the reason cited on the ground: that the best sales reps from the acquired company left. (Yes, they did, but everyone should have known and planned for that.) It’s not that B’s products don’t have value for A’s existing markets. Or even vice versa. It’s not that A’s sales reps are stubborn and retrograde, refusing by their very nature to adapt to change regardless of how much money is spent on change management, including changing how they are paid.

It’s actually simpler than all that. It’s because sales is built to take the products — the light of the sun called “Company A” — in every direction into the marketplace where those products can generate profits. Sales has a job: maximize the amount of light that falls on some planet somewhere, so said planet can cough up some more fuel for the sun. (How this happens is a mystery that stretches this metaphor beyond the breaking point and will not be explored here.)

“I dreamed a dream in time gone by…”

What is needed after an acquisition is the ability to direct sales in a very specific way: B’s products need to be sold at significantly lower cost of sales to A’s current customers. And, for full effect for the most ambitious acquirers, A’s products need to be sold into B’s presumably smaller market — without displacing B’s products, else nothing is really gained beyond some homogenization and small economies of scale.

What generally happens is A’s salespeople find that B’s products don’t sell to their current customers quite as easily as expected — and, anyway, it’s hard work. So, they keep selling what sells and, therefore, what maximized income for the sales rep. All manner of things are tried: special incentives, overlays, territorial realignment, redundant sales teams, and (all too often) quietly giving up. B’s possibly superior product gets “grandfathered” into its own customer base, and (like so many grandparents in modern society) eventually becomes an orphan to be quietly ignored as it slowly starves to death.

The dreams of product synergy — obvious and powerful though they are on paper and as slideware — evaporate, becoming clouds of unprofitable, well-intentioned activity that dissolves into a thin mist of good intentions. And then nothing.

Can this sad story play out differently? Can sales synergy ever be achieved? To find out, check back for Parts 2 and 3 of this blog series.